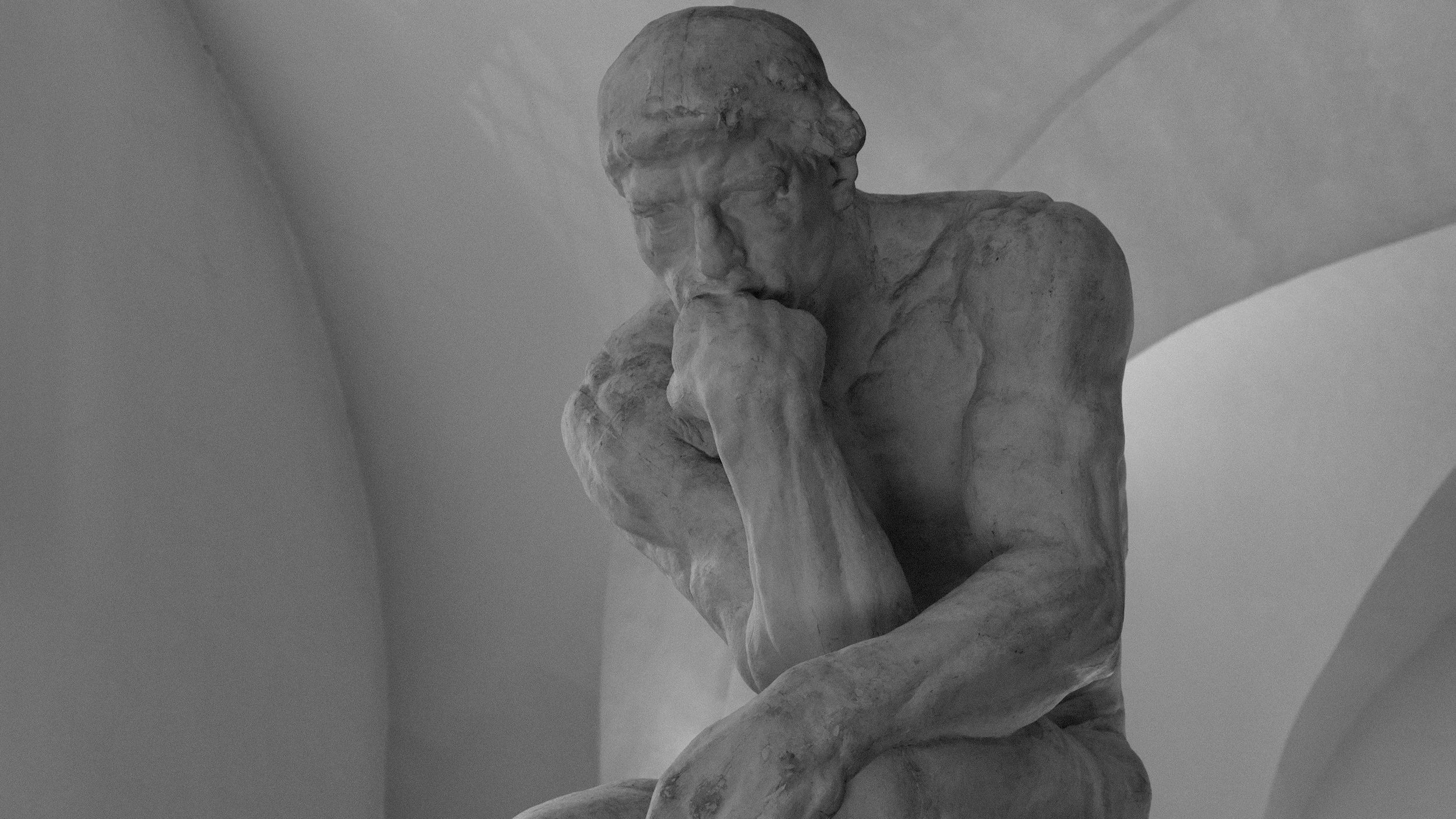

Has LeCun Been Reading Wittgenstein?

Why Philosophy Still Matters in the AI Debate

Artificial Intelligence is often framed as a purely technical challenge: more data, larger models, greater compute. Yet some of the most important questions facing AI today are not computational at all, they are philosophical.

One such question sits at the heart of current debates around Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): can machines genuinely understand language, or are they merely manipulating symbols? This is not a new problem. In fact, it was explored in depth nearly seventy years ago by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

From Logical Machines to Language in Use

Wittgenstein’s early work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, aligned closely with the ideas of Bertrand Russell, and those of logical positivists. The central premise was seductive: that the world, including human reasoning, could be fully described through formal logic and mathematics.

But Wittgenstein later rejected this view. In Philosophical Investigations, he argued that language is not a closed logical system but a social activity. Meaning does not arise from syntax alone, but from use, from shared practices, context, and what he famously called “forms of life”.

This shift has profound implications for AI.

LLMs and the Return of Mechanistic Thinking

Much of today’s AGI narrative rests on the assumption that scaling Large Language Models will eventually produce intelligence comparable to or surpassing human cognition. The argument is familiar: with enough training data and processing power, statistical prediction becomes understanding.

This position closely mirrors the mechanistic worldview Wittgenstein ultimately abandoned.

LLMs are extraordinarily good at predicting the next most likely word. But as Wittgenstein would argue, prediction is not comprehension. A system can follow rules without knowing why those rules exist or when to break them creatively.

This is why critics describe LLMs as “stochastic parrots”: fluent, convincing, but fundamentally detached from lived human experience.

Language Games, World Models, and LeCun

Interestingly, Meta’s Chief AI Scientist Yann LeCun has recently advanced a critique of LLM-centric AGI that echoes Wittgenstein’s later philosophy.

LeCun argues that intelligence requires internal world models, structured representations of how reality works, not just linguistic pattern-matching. Without grounding language in physical, social, and causal experience, AI systems remain brittle and superficial.

Both Wittgenstein and LeCun use the idea of language games to make this point. Words only have meaning within shared human activities. Shakespeare could invent thousands of new words because audiences understood them through common cultural reference points, not because those words appeared frequently in a dataset.

No amount of text ingestion alone can replicate that process.

Why This Matters for SMEs and the Creative Sector

For businesses, educators, and cultural organisations, this distinction is critical.

If AI systems do not truly “understand” context, then blind trust in generative outputs carries risk, from subtle misinterpretation to outright fabrication. This is particularly acute in heritage, education, and creative industries, where meaning, provenance, and cultural nuance matter.

At Aralia, we approach AI as a machine tool, not a surrogate mind. Data-driven models are powerful when used within clearly defined boundaries, grounded by domain expertise and transparent assumptions.

A hybrid approach, where machine learning operates alongside explicit models, domain rules, and human oversight, offers a more robust alternative. Rather than asking AI to “think”, these systems are designed to support reasoning, making their assumptions visible and their limitations explicit.

This is especially important for SMEs, who cannot afford the operational or reputational risks of opaque, black-box decision-making.

Final Thought

The future of AI will not be determined by scale alone. It will depend on whether we recognise the limits of computation, and design systems that respect the difference between language as data and language as lived human practice.

Philosophy may not ship code but it still shapes the questions that matter most.